From Cure Search:

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children, also known as acute lymphocytic leukemia or ALL, is a “liquid” tumor or cancer of the blood that starts in the bone marrow and spreads to the bloodstream (the term leukemia comes from Greek words for white and blood). ALL is the most common children’s cancer, accounting for 35% of all cancers in children. There are about 2,900 new cases of ALL diagnosed in children and adolescents (0-21 years old) in the United States each year.

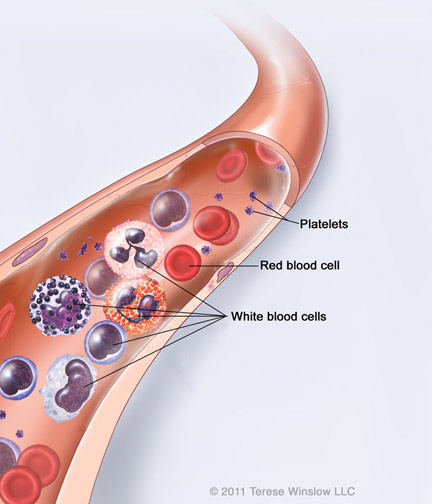

Leukemia starts in the bone marrow, the spongy internal part of bones where new blood is made. Leukemia starts when a single, young, white blood cell called a “blast” develops a series of mistakes or mutations that allow it to multiply uncontrollably. Eventually, blasts take over the bone marrow and crowd out normal blood cells. One blast soon generates billions of other blasts, with a total of about a trillion (one million times one million) leukemia cells typically present in the body at the time of diagnosis.

Symptoms of A.L.L.

Leukemia cells “crowd out” normal blood cells. It is the decrease in normal cells that produces many of the symptoms of ALL.

- Fatigue and being pale results from a decreased number of red blood cells, known as anemia

- Fever due to the disease itself or from infection because there are a decreased number of healthy white blood cells, known as neutropenia

- Bruising or bleeding from decreased platelets, known as thrombocytopenia

- Bone pain, sometimes associated with swelling of the joints

The signs and symptoms of ALL can be the same as more common children’s illnesses and many children are treated for those other illnesses before leukemia is diagnosed. Most children with ALL have symptoms for a few weeks to several months before a diagnosis of cancer is made. The time between when symptoms started and when the diagnosis is made does not change the chances for cure.

From Children’s Cancer Research Fund:

Leukemia — or cancer of the blood — is the most common childhood cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, about 2,700 children are diagnosed with leukemia in the United States each year. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, also known as ALL, is the most common form of leukemia that occurs in children. It is characterized by the presence of too many immature white blood cells in the child’s blood and bone marrow. While ALL can occur in adults too, treatment is different for children.

The term “acute” refers to the tendency of this disease to progress rapidly. “Lymphoblastic” refers to the white blood cells, which are also called lymphocytes. Normally, lymphocytes mature into an important part of the body’s defense system against infections.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, also known as ALL, is the most common form of leukemia that occurs in children. While ALL can occur in adults too, treatment is different for children.

But in ALL, something happens — researchers do not yet know what, but something interrupts normal cell development. The result is an overabundance of incompetent, “blastic” immature cells. Their presence affects a person in two ways:

1. By crowding. Lymphocytes are made in the bone marrow, the spongy tissue inside the large bones of the body. But other vital blood components are made there, too — red blood cells needed to carry oxygen to tissues, and platelets that are needed to stop bleeding through clotting. When immature lymphocytes crowd out red blood cell production, a child’s body does not receive all the oxygen it needs. As a result, he or she may develop anemia. And when immature lymphocytes crowd out platelets, the child bleeds and bruises easily.

2. By invading other organs, such as the spinal cord and brain, liver, or spleen. The presence of lymphocytes in these sites impairs function here, too.

Symptoms

In its early stages, ALL can mimic common illnesses such as the flu or a cold. The difference between ALL and an ordinary, fleeting infection is its persistence, and the fact that the child may begin to bruise easily.

Common symptoms for ALL include:

- fever

- feeling weak and tired

- pain in bones or joints

- enlarged lymph nodes as a result of the overproduction of immature lymphocytes crowding the lymph system

- bruises

Diagnosis

To detect ALL, a doctor needs to look at the child’s blood cells and bone marrow under a microscope. Several procedures are available to do this. They are:

- Blood test: This consists of withdrawing blood from a child’s arm by needle — the kind of test most children have had at least once by the time they are five years old in a routine physical exam. The blood sample is then magnified so the cells can be identified and counted.

- Bone marrow biopsy: In a bone marrow biopsy, a child is sedated and given a shot in the hip area to numb it. Once numbed, the area is ready for the biopsy. A thin needle is quickly inserted into a bone in the hip and a small amount of marrow is removed. This is examined under the microscope to determine the kinds of cells present, their developmental stage, and their population strength. Final results are generally available within 48 hours.

- Spinal tap: If it is determined that a child has ALL, a spinal tap is needed to determine if the leukemia is present in the central nervous system. The child is usually sedated and lies on his or her side and a spot in the back is numbed. A very thin needle is inserted into the space between the vertebrae — the bones of the spine — where little pockets of cushioning spinal fluid are found and then examined under the microscope. Results are usually available within a few hours.

Stages

To describe the scope of most cancers, doctors have devised a “staging system.” In it, a Stage 1 cancer is a cancer that has not spread. Stage 4 is an advanced cancer that has spread to multiple sites.

ALL is different in this respect as the bone marrow is present throughout the body. There is no staging system. Risk stratification and treatment depends on four aspects:

- the child’s age at diagnosis

- the white blood cell count at diagnosis

- whether or not the patient has been previously treated for leukemia

- results of specific tests on the leukemia cells, especially cytogenetic or chromosome tests

Based on these factors and results, children are grouped into standard, high, or very high risk categories. What therapy they receive is dictated by their risk group assignment.

Doctors generally describe the disease in one of four ways:

- Newly diagnosed: This means no treatment has been given, except to reduce symptoms and provide comfort. There may be other signs or symptoms of leukemia as well.

- In remission: This means treatment has been given and that the number of white blood cells — as well as other kinds of blood cells — is now normal in the blood and bone marrow. There are no other signs or symptoms of leukemia.

- Recurrent: This means the leukemia has come back (recurred) after having gone into remission before.

- Refractory: This means the leukemia didn’t respond well enough to treatment to achieve remission.

Replacing diseased bone marrow with healthy marrow through blood and marrow transplantation (BMT) is a technique pioneered at the University of Minnesota. In 1968, the very first successful human blood and marrow transplant was performed here, and physicians here have since done more than 3,000 transplants.

Treatment options

The following therapies are available for treating ALL:

- Chemotherapy: The most accepted and widely-used primary treatment for ALL is chemotherapy. This refers to the introduction of cancer-fighting drugs into the blood stream by mouth, or through a needle into a vein or muscle. It is a “systemic” treatment — meaning it treats the whole body, or system, because the circulating blood carries the drugs throughout the entire body. In ALL patients, the drugs also are injected into the fluid surrounding the spine and brain (usually in an area of the spine) in a procedure known as “intrathecal chemotherapy.”

- Radiation: In some cases, radiation is used. This therapy relies on a beam of high-energy particles, such as X-rays, directed at the cancer by a machine outside the body. The assault from this concentrated energy kills cells and reduces tumor size. Radiation therapy is often reserved for ALL involving the central nervous system or the testes, or for patients with T-cell disease.

- Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Replacing diseased bone marrow with healthy marrow through blood and marrow transplantation (BMT) is a technique pioneered at the University of Minnesota. In 1968, the very first successful human blood and marrow transplant was performed here, and physicians here have since done more than 3,000 transplants. Through this technique, diseased marrow is killed with high doses of chemotherapy, and sometimes with radiation as well. Healthy marrow or stem cells are then taken from a donor whose tissues match the patient’s tissues. This donated marrow is transplanted through a needle in a vein. Marrow cells then seek the right places in the bones to replace diseased marrow. An internationally recognized leader in bone marrow transplantation, the University of Minnesota BMT program is experiencing increasing success.

Treatment phases

There are generally four phases of treatment for ALL. They consist of different kinds, doses and combinations of cancer-killing drugs and radiation. They are:

- Remission induction chemotherapy: This stage uses anti-cancer drugs to kill as many of the leukemia cells as possible to cause the cancer to go into remission. It lasts about one month.

- Consolidation, or Central Nervous System (CNS) Prophylaxis: This is a preventive therapy to stop the spread of the cancer to the brain and spinal cord, even if none was detected there at initial diagnosis. It consists of intrathecal and/or high-dose systemic chemotherapy. Radiation therapy to the brain also may be given for this purpose. CNS prophylaxis also may be given in combination with the following treatment phase. Length of this phase can vary, but it generally lasts one to two months.

- Intensification Therapy: This begins once a child goes into remission. It consists of high doses of chemotherapy intended to kill any remaining leukemia cells. It may be given one or two times, lasting about two months each time.

- Maintenance Therapy: This relies on the use of chemotherapy for several years to maintain the remission. For girls, total treatment lasts just over two years. For boys, total treatment lasts just over three years.